How Australian Music Lost Its Global Relevance

Australia is the country that you used to know

Between 2011 and 2020, Australia turned 20 artists into global superstars — an average of two artists per year. However, since 2020, that number is zero.

Australia is the country that you used to know.

In 2017, Richard Kingsmill left his role as Music Director of triple j, the radio station responsible for kickstarting the careers of 15 of the 20 Australian global breakouts between 2011 and 2020.

While he was in charge, artists which were added to high rotation got a lot of spins. Speaking to The Black Hoody, label sources reported that high-rotation songs received 120-140 spins ten years ago vs the 60-80 spins they get now.

It could be argued that Kingsmill had the most influence on breaking Australian artists than anyone else in the country. The songs Kingsmill added would get massive support on triple j, cross over to commercial radio, then dominate the ARIA charts.

Record labels could then carry that momentum and story globally, using it to join international tours, festival lineups, co-signs and press opportunities.

triple j was the flame to the bonfire. Was being the operative word.

A Country Built On One Radio Station

However, when Kingsmill left his post as music director, so did the flame. When triple j lost its curation, its audience followed.

Unmade reported that between 2014 and now, the number of the station’s targeted 18 to 24-year-old listeners had fallen 55%, and now only 10,000 people are listening to the station at any one time. Think about that: most mid-tier artists will get more reach on their Instagram posts than a play on triple j.

Whatever the reason for the triple j audience decline, the double blow of both a reduced audience size and songs getting less spins per week means it’s now near impossible for triple j to create hit songs by themselves.

This reality has sunk the Australian music industry’s export capabilities, as most music festivals and major record companies previously built their whole businesses on triple j play.

The Death Of Australian Music Festivals

Most of Australia’s most prominent festivals; Splendour in the Grass, Groovin’ The Moo, Falls Festival, and Spilt Milk, have either folded or been cancelled.

These aforementioned festivals all had one thing in common: they were built on triple j artists and audiences. To make matters worse, at the same time triple j’s ratings fell, so did the Australian Dollar; a double blow for Australian music festivals.

The depressed AUD meant festival promoters couldn’t book international headliners anymore. Not only had they lost the radio station that built their artists and ticket buyers, they also lost their buying power (AUD) to import internationals.

Festivals were stripped naked right before the snowstorm hit.

A rare exception to this rule is Laneway Festival. The touring festival across Australia and New Zealand has managed to build a business that is not dependent on headliners or triple j playlisting.

Laneway’s festival co-founder and promoter Danny Rogers told The Black Hoody that, “Laneway was always primarily focused on trying to create a cultural event that prioritised future icons vs. artists that were already massive headliners.”

“A lot of people think you can build festival line ups on radio play and data,” Rogers added, “but that doesn’t create a culture, it feels homogeneous and pretty samey. We have passed on so many acts over the years which would have sold us more tickets but they didn’t fit what we were trying to say as a festival.”

When speaking with The Black Hoody, Rogers said he is grateful for triple j, who have been “important” partners to Laneway since its inception in 2005. However, he stressed they never let triple j’s playlisting dictate the Laneway lineup.

“triple j was always an important partner but we didn’t let them govern what we did, for example, we booked The 1975 before triple j ever played them,” he said.

An Australian Chart With Few Australians

Last year, ARIA CEO Annabelle Herd acknowledged a problem: not enough Australian artists were topping their charts; “There are simply not enough Australian artists – let alone new Australian artists – breaking through with their home audience,” she said.

The ARIA charts have become consumption charts. They mostly chart songs people listen to rather than buy, a new phenomenon caused by streaming.

For all of music history, we never charted how many times people played their new Eminem album when they got home from the record store, only how many albums Emimen sold. However, ARIA counts “equivalent sales” every time a track hits a certain number of streams — which is the same as counting a song every time it is played on your record player or a radio station. This is vastly different to actually buying a record.

ARIA doesn’t differentiate between a stream that a fan seeks out to play, saves to their library, and actively spins regularly, vs. a song that is auto-played via the algorithm or on a massive platform-promoted playlist. It begs the question: how are they of the same value?

Shouldn’t a passive stream (the auto-played / algorithm-fed play) be treated like a radio spin? And shouldn’t the active streams be treated like a purchase, or part of a purchase?

The ARIA chart system is weird and flawed, making it nearly impossible for Australian artists to compete with internationals who dominate the passive listening platform algorithms.

Without Australians getting their fair shake at the chart, managers and labels lose a chart story to take to other markets.

How Did ARIA End Up Here?

This is where it gets curious. Herd, the ARIA CEO, is clearly frustrated, but ARIA is also funded by the major labels, who are all represented by local teams that receive bonuses tied to the success of local artists.

Local major labels should want the charts fixed as soon as possible, too, and they’re the ones sitting on the ARIA board.

Everywhere you look, the ARIA board and the CEO are incentivised to fix the chart system, but nothing gets fixed. They continue to allow internationals to invade Australia and take all the opportunities from local artists.

My guess is that the local representatives from the majors on the ARIA board are hand-tied by their multinational owners. Perhaps the international offices at Universal, Warner, and Sony don’t want the ARIA charts to change as they favour their global stars.

However, the problem gets worse. The few Australian artists who reach #1 on the ARIA charts no longer see any global uplift from that achievement.

Andrew Stone, manager of Sheppard, (which broke out globally in 2014), and Lime Cordiale, (which secured two consecutive #1 Albums on the ARIA charts), told The Black Hoody that, “the impact of a #1 was much more noticeable domestically rather than internationally.”

In fact, all the artist managers The Black Hoody spoke to said a #1 ARIA album no longer moved the dial internationally like it did 10-20 years ago.

ARIA is a local brand serving local record labels, but it needs to find global relevance to move the dial for Australian artists overseas.

Australian Major Labels Are Stuck

So, where does this leave the three majors in Australia?

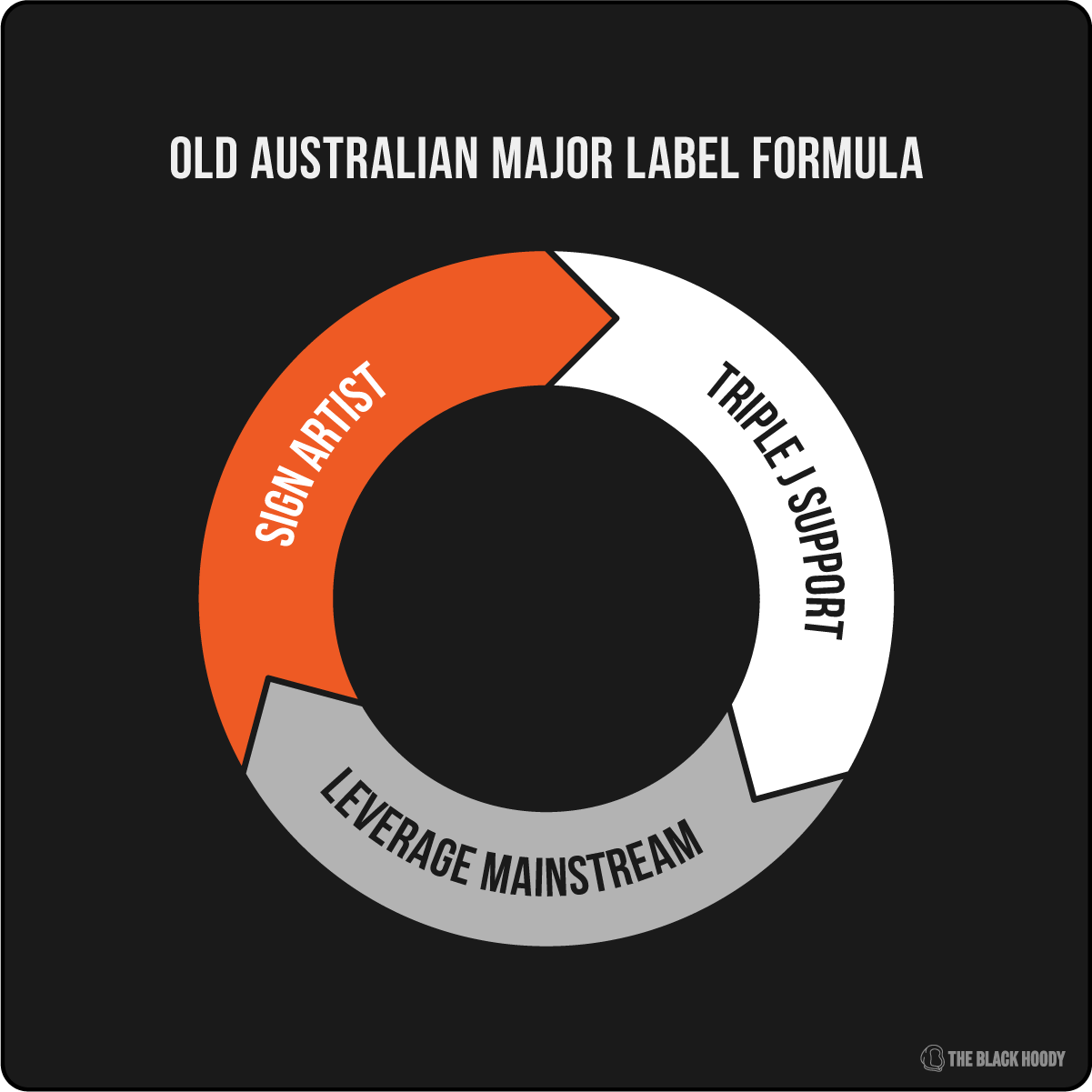

When triple j was at its peak in 2019, the Australian major label formula was simple: sign an artist, get triple j support, leverage the mass media spots and commercial radio, repeat.

Often, majors wouldn’t even sign artists until triple j supported them. Ten years ago, I managed an artist who was rejected by all the labels for the first five years of his career until he got his first bit of triple j play—then suddenly, there was a massive bidding war.

No major label has managed to break a local artist globally since 2020. There have been a few moments like Masked Wolf, who had some global traction on TikTok when “Astronaut in the Ocean" became a sleeper hit in 2021. But he couldn’t maintain his momentum following his viral moment.

Artist manager Andrew Stone believes this trend of flash-in-the-pan TikTok artists is because labels aren’t investing enough in the artist to capitalise when lightning strikes.

“If you have one breakthrough viral moment, you have to be ready with the next ten songs because that’s where you have the real opportunity to create history […]. If the next song you release after your viral moment is bad, then it’s going to be very hard to ever get the momentum back,” Stone said.

It will take one of the majors to think outside the box and create a new artist development and marketing method to break Australia's downward global export trend. Most importantly, it will take patience and support from the international head offices to allow them to continue investing, experimenting, and innovating.

Without this continued local investment, the majors in Australia will turn into low-touch distribution companies and regional PR and marketing teams for the big international acts. This would be a commercial mistake for the majors, and leave the door open for a new player who figures out how to break Australian acts again.

Reclaiming Australian Dominance

ARIA To Be A Global Pioneer

ARIA needs to fix its chart system to stop the international invasion, and quickly.

It needs to do something no other major chart in the world does: give its local artists something meaningful when they get a #1.

Because the Australian population is so small and isolated from the rest of the world, ARIA should take on an export responsibility where they put together a “#1 package” for every artist who gets a #1 spot.

This package could include international opportunities, such as billboards in other markets (in the same way YouTube Music and Spotify does), radio spots, and international editorial support on platforms.

Imagine if every artist who got a #1 ARIA album automatically got a billboard in Times Square or on Hollywood Boulevard, plus interview spots on radio stations and variety shows in the US and UK, and editorial support in other markets on streaming platforms. The ARIA charts would then move the dial globally for Australian artists with every #1.

These are just some ideas, and of course, all are either very expensive or nearly impossible to pull off, but they’re nearly impossible, not impossible.

If ARIA were to create an “international wishlist” for this #1 package of 100 or so ideas, they would be able to pull off at least 4-5 of them with enough hard work and resources, and all you need is 4-5 good opportunities to move the dial for an artist.

The issue is that the majors fund ARIA, which would require them to reach into their pockets to give ARIA more funds and resources to pull this off. And who knows if they would entertain that.

If they don’t, however, the Australian majors may remain stuck.

triple j To Get Back To Creating Hits And Celebrity Presenters

triple j must focus on picking and spinning winners and booking world-class, hilarious presenters who are born entertainers. Something their new Head of Programming, Ben Latimer knows a lot about.

Throwback to when Matt Okine took over the breakfast show seat in 2014

Picking music and hosts with too much focus on diversity and social agendas compromises the quality of the entertainment offering.

Diversity is essential, especially for a public broadcaster. However, nothing should go to air (either presenter or song) unless it’s the best Australia offers. The listeners are switching off at an alarming rate, so continuing the current path will be the death of the station.

The bottom line is, all radio stations now need a differentiated product from streaming. Why would you turn on the radio to just listen to music? That makes no sense.

Unless there is something about the station that makes them culturally relevant, like a tastemaker on air with a big following or hosts like Matt and Alex or Kyle and Jackie O, there’s no reason to tune in.

The playbook for triple j might not be complicated; they might just need to go back to what worked for them before, focusing on more spins for fewer songs and getting genuine stars as hosts:

In saying this, I’m very bullish on Emily Copeland’s hire at the ABC (triple j’s parent company). Emily was appointed Head of Music at ABC in May of this year and has an incredible brain for both radio and growing audiences. If given the empowerment she deserves, her vision could do wonders in the reimagining of one of the industry’s most beloved brands.

Turning triple j around might be the most challenging job in Australian music; enforcing cultural and editorial change fast enough at a government station feels nearly impossible. Unlike the private sector, she can’t just move quickly and replace staff who don’t buy in; government jobs are safe even if you’re underperforming, which makes leadership and change management all the more difficult.

Emily Copeland, head of Music for ABC

Majors To Go From Hit Machines To Career Engines

Like the big tech companies, which are investing in AI and VR to discover their new future, major labels in Australia must also invest in discovering their new future.

What will marketing and development look like for Australian majors in a post-triple j era?

It is clear that spending more money on TikTok creators in this market is not the long-term answer; they need to find something new.

“The old-school mentality of let’s sign it, try to get a hit and see what happens, doesn’t work anymore,” Andrew Stone said. “Now you don’t know if an artist is going to be a hit until you’re two records in. [...] So you need companies that think and invest long term; but it also means artists need to be willing to sign long term rights too.”

Majors must become Venture Capitalists: invest now for a payoff in 8-10 years. That’s a massive shift in thinking from the sign-but-drop-them-if-it-doesn’t-work model that the majors have adopted for decades.

Australian Music Festivals Will Be Back

I’m less concerned about Australian music festivals. They’re the fruit of the tree, but without the tree, there is no fruit.

Once Australian artists start breaking out again, the audiences will be there, and festivals will come back to service them, but we need to start planting trees first.

Hi. American musician here.

Most Americans love the stuffing out of Australians and Australian artists, when clearly identified as such (or sometimes even not, as evidenced by the influx of male "bro-country" singers and American football players in the specific position of "punter"). This is from a combination of good niche-fitting and a certain air of "exoticism" that Australians carry when over here, that Americans remain enthralled by.

Platforms like TikTok homogenize, and often decontextualize; and presenting culture (like music) devoid of context (like origin) just doesn't work.

Triple-J needs to "triple down" on the "Australian-ness" of its playlists and offerings; become the beacon of "Brand Australia" that the big worldwide labels look to. Whether that's by Canadian-style regulated "Can-Con" quotas or more informal ones, whatever works politically; but find the artists who light up the room and Send Them Up Through America.

Hook them into the specific infrastructures of their genres and niches, yes, but Send Them here.

Many will do well, if they know how to lean into their Oz-ness enough to distinguish themselves from the pack. Those that do, can bring that success as credibility to use back home.

Awesome read, I really enjoyed the perspective. It’s such a thought-provoking subject and something I’ve been spending quite a bit of time on trying to understand, especially from a psychological point of view.

If you take localisation out of the equation (talking about the frequency of Australian based artists achieving global success), my bet is that the surge in platforms has led to a behavioural shift in how people encounter and feel about music. It's a different value proposition to what it was back pre-platforms. You hear a song, it makes you feel a certain way, you don’t care if it’s popular or not, but you save it because it means something to you. You’re choosing to invest into a song and an artist because of the way they make you feel, the product is the feeling. The country or location really doesn’t mean anything.

There was a super interesting quote from Gustav Söderström on a product podcast I enjoy: “The internet started with curation, often user curation. So you took something, books or music, you digitise it and put it online and you ask people to curate it. That was Facebook, Spotify and so forth. After a while the world switched from curation to recommendation, where instead of people doing that work, you had algorithms. That was a big change that required us and others to actually rethink the entire user experience and sometimes the business model as well. And I think what we’re entering now is we’re going from your curation, to recommendation, to generation”.

It’s interesting in the context of the article in that traditionally Triple J (and friends) would curate music that I had a high chance of enjoying. Since I valued the source, I perceived the music to be more enjoyable or “worth” more to me. It was exclusive, it held meaning outside of the music itself (social ties, or being informed), and because I had it, it was part of my collection. It felt personal. This unconscious bias was the differentiator in my view.

That might have been the 2010s. Since then the job that radio serves for me is a stop gap between travelling, being in an environment where I have to listen to it, and actually being able to listen to the music I care about. If I am looking to find something new, it’s an explicit choice, genre driven, hyper personalised, within proximity to an artist I already know (think Matisse and Sadko to Third Party). We collect songs that are given to us based on the songs we’ve saved in the past because it’s the product of probability. I trust my listening history and past behaviour to know more about my taste and what I want to hear vs. a random presenter on the radio.

When you look at the initial quote from Gustav, the curation > recommendation > generation is just full circle. We’re going back to having access to track lists that are made for us, except we’ve removed the human curation aspect, and recommendation has become generation for an audience of me. It’s personal.

What platforms are doing, when done well, is creating the perfect execution of the behavioural model from Dr. BJ Fogg. A combination of a motivation (do I like the music), an ability (can I become a fan or connect at some level) and a prompt (the platforms provide this, i.e. saving or liking). Traditional radio offers none of this, yet there’s significant opportunity to identify what the latent demand is for those who do listen to radio and invest in more in what does deliver real value to listeners.

Apologies for the manuscript.